On Wednesday, during a hearing of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee on the winter floods, Paul Leinster of the Environment Agency told MPs that vulnerable stretches of coast could be abandoned to the sea. The process, which goes under the dreary name of managed realignment, would change the shape of Britain – with thrilling consequences.

Last weekend my old friend Richard North (I knew him well before he became Richard D North, let alone “the stand-up philosopher”) showed as a new wetland in the making to the west of Selsey, one which could soon rival the marvelous Pagham Harbour to east of the town. A few months ago we could have walked all the way along the shingle shore to Bracklesham. Not any longer. In November, the Environment Agency breached the old sea defences. This was the final act in the two-year Medmerry Managed Realignment Scheme, which involved the construction of 4 miles of new sea walls, some stretches of which are over a mile inland.

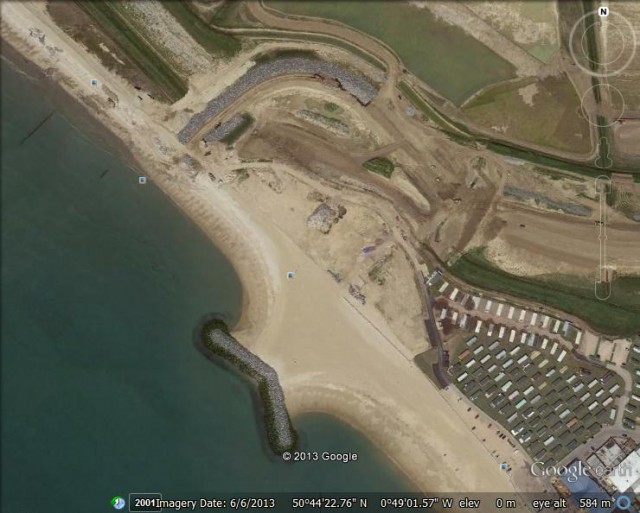

The Medmerry scheme before the breaching of the sea wall. Much of the area to the north-west of the caravan park is now submerged at high tide.

The area looks scruffy still, much as you would expect after such dramatic gouging and reshaping – over 60,000 tonnes of rock were imported by ship – but already nature is taking hold. There was a mixed flock of waders on a sliver of land that hadn’t been submerged by the high tide. Fifty or so lapwings, their oblong wings flapping black and white against the grey skies, circled above some damp pasture beyond a caravan park. When we reached the narrow breach in the shingle wall a few hundred knot zipped overhead, as though they were late for a meeting. We also saw two red-breasted mergansers and a little egret. No doubt we’d have seen more birds if we’d hung around.

Allowing the sea to reclaim the land may be a strange form of flood protection, but that’s precisely what it is. Medmerry was at such risk of future flooding that the Environment Agency decided it made better sense to build new defences inland rather than protect the old seawall. This will improve flood protection for over 300 homes, a water treatment works and the main road into Selsey.

Since 1992, the UK has been obliged by the EU Habitats Directive to prevent net losses of salt marsh. The new salt marsh at Medmerry, which will cover some 450 acres, will make up for salt marshes lost to development in the nearby Solent. Besides creating a large area of intertidal wildlife habitat, which will be managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), the scheme is setting up a network of footpaths, cycleways and bridleways.

The Environment Agency has invested £28 million in the Medmerry realignment scheme, and Bunn Leisure, owner of one of the largest caravan sites in England, has stumped up £16 million to protect its property. So this has cost serious money. However, I can’t think of any other recent major development scheme – I wouldn’t expect Mr Bunn to appreciate this point – whose impact on landscape and wildlife will be so beneficial.

If sea levels rise as a result of climate change, then we will see a lot more managed realignment schemes such as the one at Medmerry. Let’s hope they don’t ruin it by carpeting the surrounding landscape with inefficient and unsightly wind farms.

You can get daily briefings about the bird life at Selsey Bill and on the Manhood Penisula here.