When we had finished breakfast Tom Yandle suggested we head up the hills behind his farmhouse to see if there were any red deer about. After a short, steep drive through woods smelling of wild garlic we surprised 15 or so hinds. A couple of fields later we came across a herd of over 100 deer. As we approached they streamed gracefully into the thick woods beyond.

“One of the reasons why there are so many deer on these farms is because the hunt doesn’t come here now,” said Tom, who has spent his life farming near Dulverton and hunting with the Devon and Somerset Staghounds. The hunt doesn’t come as the farms are close to Baronsdown Sanctuary, established by the League Against Cruel Sports in 1959 as a way of protecting red deer from the hunt, and land where the League owns the hunting rights.

Talk to farmers on Exmoor, or anybody involved in managing the red deer, and they will bridle at any mention of the League. Its activities have deprived hunters of land on which to hunt, but that’s a relatively minor issue. What really concerns them is the health and welfare of the deer in and around Baronsdown Sanctuary.

Not a great photo, but you get the picture. A herd of 100 or more red deer in a farmer’s field near an area where the League Against Cruel Sports owns the hunting rights.

In 2002, a former League employee told the Daily Telegraph that during a 12-month period 107 deer were found either dead or dying of starvation or disease at Baronsdown. At one time there were some 350 deer in the 225-acre sanctuary, and the League’s refusal to cull the herd meant that the land had been turned into a sort of rural slum, creating perfect conditions for the spread of disease. To put this in context, the National Trust has a herd of approximately 430 red deer on an estate covering some 12,500 acres.

“One year a load of stillborn deer calves were seen in the woods at Baronsdown,” said Charles Harding, the National Trust’s stalker, when we met at Tom Yandle’s farm. “And we know that red deer in the League’ s sanctuaries have had serious problems with disease, especially lungworm and bovine TB. That’s what happens if you don’t manage the herds properly.”

In 2008, the Exmoor National Park Authority commissioned a report on the health of red deer. Between January 2000 and September 2008, there were 156 submissions to the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) of suspected bovine TB cases from Devon and Somerset. Of the 97 confirmed TB cases, 88 were in red deer, and all but 11 of these, or 86%, were from deer found within two kilometres of Baronsdown. “The distribution of these cases is highly significant,” wrote the ADAS consultants, adding that they constituted “a serious compromise of animal welfare.” Bovine TB is one of the nastiest and most debilitating diseases, causing long-term suffering and eventually death.

Doing nothing is a form of cruelty

Nobody, as far as I know, is suggesting that the League was wilfully cruel. However, the way in which the League has managed Baronsdown shows that it has no understanding of the basic principles of population biology. This is what its former chief executive, Douglas Batchelor, said in 2007 when he was interviewed for a BBC programme about the poor health of the deer at Baronsdown: “We are doing everything we can to do what the advice is, which is let the wildlife be wild and don’t interfere with them and don’t seek to ‘manage them'”.

This would be fine if the natural predators of red deer – the wolf in this country – were wandering around Exmoor and doing their carnivorous business. But they disappeared from the landscape many centuries ago, so now it is up to us humans to control and manage the deer. If we don’t, the job will be done by disease and famine: witness what happened at Baronsdown.

On our way to Exmoor, we’d dropped in to see John Webster, Emeritus Professor of Animal Husbandry at Bristol University and one of Britain’s leading experts on animal husbandry and welfare. He still has concerns about the length of time it takes staghounds to bring a deer to bay. “In the past, deer were clearly pushed beyond a state of exhaustion, which is cruel,” he said, “but evidence presented to the Independent Authority on Hunting showed that the hunts have been doing it more quickly, which is a good thing.” Significantly, he believes the red deer on Exmoor – leaving aside those clustered around Baronsdown – to be one of the healthiest and best managed populations in the country. “So in a utilitarian sense, the hunts have been very good for the species,” he said.

The Devon and Somerset Staghounds can no longer go out with a full pack of hounds, but under exemptions in the Hunting Act they can use two hounds to pursue deer for the purposes of research and observation, flushing and shooting, or capturing injured or sick animals. Unfortunately, this compromises one of the key functions of the hunt, which is to move deer around, partly to ensure that damage to crops and pasture is shifted from one area to another; and partly to keep the genepool in good health by ensuring that sedentary stags don’t breed with their own progeny.

Farmers are part of the ecosystem too

When stag hunting began in Exmoor in 1855, there were thought to be around 75 red deer. Within 20 years or so the population had risen to over 1000. Now there is a stable population of some 3000. Their survival hinges entirely on the goodwill of farmers. There is nothing, in law, to stop farmers shooting deer on their land, but they tolerate the damage caused by the deer precisely because of the presence of the hunt.

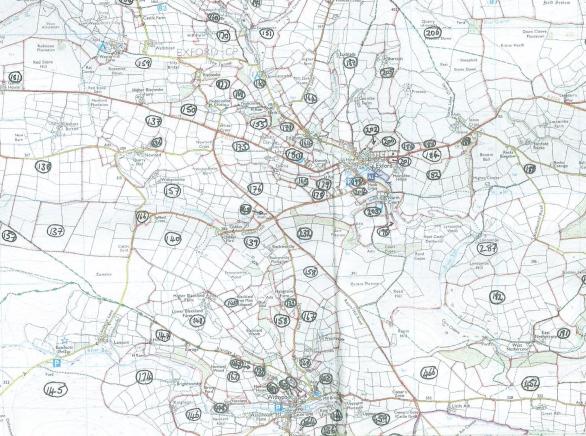

Over 700 Exmoor farmers signed a Declaration stating that hunting was the best way of managing red deer. The numbers on the map indicate farms whose owners or tenants signed the Declaration.

Prior to the passage of the 2004 Hunting Act, which banned hunting with dogs, 717 farmers and woodland and moorland owners from Exmoor signed a Declaration which was presented to the House of Lords. This stated: “The existence of a strong and healthy herd of red deer in this region depends on the continuation of the hunt. Because of deer hunting, the farmers preserve and protect the herd despite suffering both damage and economic loss.”

“People here see the deer as a community asset, and that’s why they want to protect them,” says Hugh Thomas, chairman of the Exmoor and District Deer Management Society. “Even people who would be happy to shoot deer when they’re on their land don’t, because they think the deer belong to the hunt and the community.”

Before we left Exmoor, we visited a non-hunting farmer in a hamlet above North Molton. So far this year Dennis Jones hadn’t lost a single lamb – he has 1800 ewes and 60 head of suckler cattle – and he attributed this to the lack of foxes, which are controlled by local shoots, and the fact that he lambs indoors. But he was concerned about the high incidence of bovine TB in badgers. “It’s not that I want to get rid of them all, but we need to manage them, to control their numbers,” he said. “It’s the same with the deer.”

He regularly sees 80 or more red deer grazing on his land. “Like most of my neighbours, I put up with the damage they do, because we love seeing them,” he said. He used to grow barley as livestock feed, but he no longer does as the deer did so much damage. It’s not even worth growing root crops because the deer will get them first.

This past season, the Devon and Somerset Staghounds frequently hunted over his land. However, in years gone by he would have seen them even more often, as he and his neighbours would frequently call on the hunt to track down and dispatch sick and wounded deer. “When they use just two hounds, they often can’t find the deer, especially in thick woodland, so I don’t bother calling them now when I see wounded animals,” he said.

What would happen, I asked, if hunting was banned altogether, as the League and other animal rights organisations would like? “If there was no more hunting, many farmers wouldn’t put up with the damage the deer cause,” replied Dennis. “They’d be more likely to kill them, or get others in to kill them. There would be more poaching too, and there would soon be a lot less deer.”