The authors of the Book of Leviticus were under the impression that bats were birds, and listed them alongside hawks, owls, ravens and herons as being unclean, or an “abomination” in the words of the King James Bible: as such, they were not to be eaten (11: 13–19). Modern churchgoers know that bats are mammals, not birds, but many would agree that they belong among the unclean.

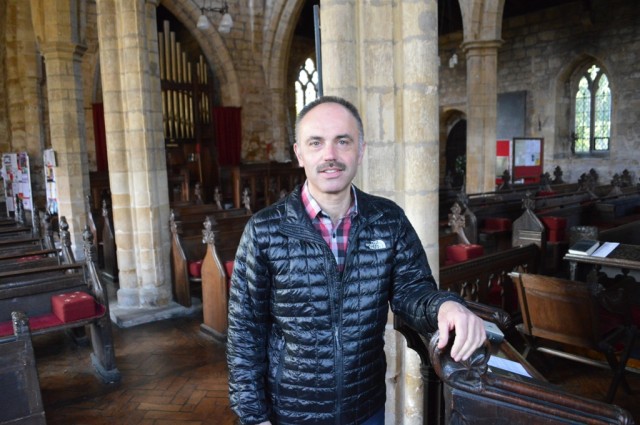

“We must have had bats here for a very long time, but the amount of mess they make seemed to increase from the late 1970s onwards,” explains Vic Allsop, churchwarden at All Saints’, a 13th century Gothic church in the village of Hoby in Leicestershire. “Now, we have to sweep up the bat droppings and wipe away the urine before services or any other event.”

You can see how bat urine has streaked the organ pipes

Bat urine has mottled the gold-leaf paint on the organ pipes. In places the stone walls are streaked black with bat droppings and most of the woodwork is pocked with bat urine. The 14th century Villiers Brass, now covered for protection, has been scarred by droppings and urine. And in summer the 500 or so bats which live above the wooden ceiling sometimes give off an acrid stench.

Five species have taken up residence here, the rarest of them being Daubenton’s bat. A colony of around 300 occupies the space between the lead roof above the north aisle and the wooden ceiling. The church isn’t just a roosting site, it is a “proving ground” for bats. The young practice their flying here before they head out into the wider world in search of insects.

“The congregation is small and elderly, and they find it dispiriting having to clean up the mess left by the bats,” says Vic. “We feel as though we are fighting a losing battle.” Ideally, All Saints’ would like permission to exclude the bats, but that’s not going to happen. All bats are fully protected under European and UK law and any act considered prejudicial to their survival – such as denying access to a roost – is deemed illegal.

A familiar story

Approximately 6,400 churches and chapels in England are being used, in one way or another, by bats. As their natural habitats – caves and woodlands – have come under threat, building such as churches have assumed ever greater importance as roosting sites. At the same time, many churches face the perennial challenge of keeping their structures in good repair. The presence of bats makes this all the trickier. If a church with bats wishes to conduct any form of building work it must consult Natural England, and they will advise the church to hire the services of a licensed ecologist. Without their involvement, planning authorities and organisations like English Heritage will not allow the work to go ahead.

Vic Allsop accepts that the bats are here to stay, but he believes the church deserves a better deal

When All Saints’ applied to English Heritage for a grant to replace the old roof above the north aisle – home to the Daubenton’s bats – the church was obliged to hire an ecologist, without whose testimony there would have been no grant. The ecologist charged over £3000. If you want to read a detailed expose about the thriving bat industry, then have a look at Nicholas Coleridge’s article in the Daily Telegraph about his experience when he wanted to restore an old barn.

Vic knows that All Saints’ would never be granted a licence to exclude the bats. But he does believe Natural England, as the statutory body in charge of wildlife conservation in the country, could do more to help. “I’d like Natural England, and others involved in bat conservation, to come to the table and talk openly about the problem,” he says. “I’d like there to be a partnership, and a constructive conversation about how we – the bats, the church and the conservationists – can coexist. That simply hasn’t happened.”

I ask Vic whether some financial assistance would help.

“Yes,” he replies. “It would make a huge difference if we had a contribution towards cleaning the church, because it’s very time-consuming, and I think it’s unfair asking the elderly congregation to keep doing it voluntarily.” It would also be reasonable if Natural England helped with other bills too. For example, replacing the gold leaf on the organ pipes costs at least £300 each time. At present, the church is paying for the privilege of being peed on.

To put this in context, farmers in England receive over £500 million a year to participate in a variety of agri-environmental schemes whose purpose is to help conserve wildlife. These schemes include measures, among other things, to improve habitat for bats. Yet not one penny of this goes to churches which are acting, whether they like it or not, as bat caves.

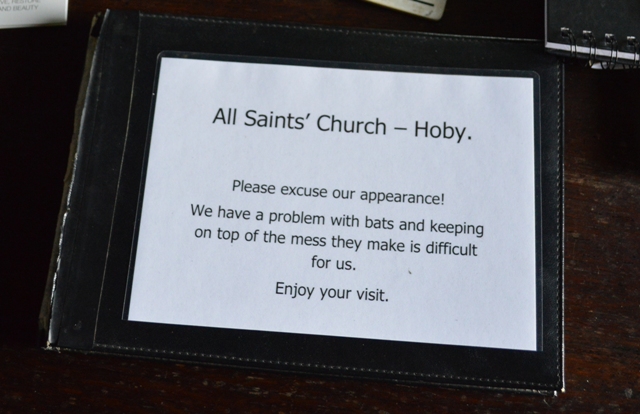

A sign of the times